DEET is an active ingredient found in a variety of insect repellents. IR3535 works for up to eight hours and is nearly as effective at repelling insects as DEET. IR3535 is considered to be a safer alternative to DEET. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has concluded that IR3535 is practically non-toxic to humans through normal use.

History Efficacy Mode of Action Toxicity

|

|

|

|

|

| Product Name | Repel 100 | Sawyer Maxi DEET | 3M Ultrathon | Repel Wipes |

| Price | $8 | $10 | $7 | $5 |

| Size | 4 ounces | 4 ounces | 1.5 ounces | 15 wipes |

| Application | Pump Spray | Pump Spray | Lotion | Soft Wipes |

| Use On | Skin | Skin | Skin | Skin |

| Active Ingredients | DEET | DEET | DEET | DEET |

| A.I. Concentration | 98.11% | 98.11% | 34.34% | 30% |

| Extended Release | no | no | yes | no |

| Duration | 9 – 12 hours | 9 – 12 hours | 9 – 12 hours | 4 – 6 hours |

| Product Label | ||||

| MSDS | ||||

| FleaScore | ||||

| Reviews |

- Prices are approximations based off of Amazon.com prices at the time of publishing.

- FleaScores are based off of product details (price, size, active ingredients, etc), as well as reviews aggregated from 3rd party sources.

Summary

DEET is a broad-spectrum insect-repelling compound. Since 1946, DEET has been considered the “gold standard” of insect repellents thanks to its high efficacy and favorable toxicological profile.

DEET offers protection from numerous biting arthropods, including fleas and mosquitoes. Upon application to exposed skin, 99% of mosquito bites are prevented for up to 12 hours.

Details

DEET

Chemical Overview

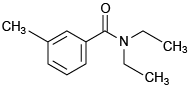

| Chemical type | Pesticide – insect and acarid repellent |

| Chemical family | N,N-dialkylamides |

| Common names | DEET, diethyltoluamide, N,N-Diethyl-m-toluamide |

| INCI name | Diethyl Toluamide |

| IUPAC name | N,N-Diethyl-3-methylbenzamide |

| CA name | Benzamide, N,N-diethyl-3-methyl- |

| CAS No. | 134-62-3 |

| Manufacturers | MGK Company, S.C. Johnson, Clariant Corp., Schering-Plough, Morflex Inc. |

| Molecular formula | C12H17NO |

| Molecular mass | 191.27 g/mol |

| Physical state | Liquid |

| Odor | Faint characteristic odor |

| Color | Slightly white to amber |

| Molecular Structure |  |

DEET is a solvent and plasticizer. It can damage synthetic, petroleum-based materials that it comes in contact with such as plastic, vinyl, rayon, acetate, pigmented leather, spandex, rubber, elastic and varnished finishes. DEET will not damage natural fibers such as wool, nylon and cotton.

History

The use of insect repellents dates back to before the Middle Ages, when people used smoke, tar and plant oils to deter nuisance insects.

At the start of World War II, the U.S. military was using a repellent called “6-2-2”. However, it failed to provide adequate protection from insects.

Research that led to the synthesis of DEET began in 1941. The Surgeon General requested that the USDA study how to control chiggers with insecticides and repellents.

During the Second World War, malaria outbreaks in oversea troops became a substantial problem. This further motivated the research for discovering new, high-efficacy, synthetic insect repellents.

Prior to World War II, the four main insects repellents were citronella oil, dimethyl phthalate, Inalone and Rutgers 612. The latter three were combined into a product called “6-2-2”, named after their relative concentrations in the formulation. “6-2-2” was used by the U.S. military when World War II began, but it often fell short of providing adequate protection from insect bites.

Research that led to the synthesis of DEET began in 1941. At this time, chiggers were becoming a problem for military personnel during training in the United States. As a result, the Surgeon General requested that the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) study how to control chiggers through the use of insecticides and repellents. Together, the USDA and the Department of Defense (DoD) began researching potential high-efficacy insect repellents.

During the Second World War, insect repellent research was further propelled forward, motivated by a substantial number of oversea American troops becoming afflicted with mosquito-borne and chigger-borne illness, namely malaria and brush typhus. A more effective and longer-lasting alternative to botanical compounds and “6-2-2” was needed to protect troops.

Malaria has been a problem for the U.S. military throughout history. During The Civil War, 10,063 troop fatalities were caused by malaria. In 1898, during the Spanish-American War, there were 90,461 cases of malaria and 349 resulting deaths. In World War I, over 194,539 man-days were lost due to malaria.

During World War II, there were a total of 492,299 cases of malaria. Over 6.5 million man-days were lost.

In World War II, American troops began being stationed in highly malaria-prone areas of the world. Battling mosquito-borne illness became a substantial problem for the United States Army Medical Department. For months in 1943, 80% of the 1st Marine Division had to be hospitalized, rendering the unit obsolete. Many infantry divisions in Guadalcanal had over 50% of their troops develop malaria. At one point in the China Burma India Theater, 55% of hospital beds were occupied by malaria patients. From 1942 to 1945, there were a total 492,299 cases of malaria, with many relapses. The minimum duration for a hospital visit was 13.6 days, resulting in the military losing at least 6.5 million man-days.

Once Japan entered the war, American troops began engaging in jungle-warfare in the Far East. This resulted in scrub typhus outbreaks caused by chiggers. From 1943 to 1945, there were 5,663 cases of scrub typhus and 234 resulting deaths.

Between 1942 and 1945, the USDA tested over 7000 potential compounds for repellency. Many compounds were chosen at random and from government, commercial and university laboratories. The compounds which displayed valid insect repellency effects were then tested for skin irritation and toxicity.

In 1946, DEET was synthesized in a breakthrough by the Agricultural Research Service, the chief scientific research agency of the USDA. It was then subsequently patented by the U.S. Army.

DEET was discovered during a screening process that tested over 40,000 chemicals.

In 1957, DEET was registered with the EPA and became widely available to the general public.

In 1946, DEET was discovered in a breakthrough by the Agricultural Research Service (ARS), the chief scientific research agency of the USDA. Over 40,000 chemicals were tested and screened during the process of discovering DEET. DEET was shown to have excellent repellent capabilities and a favorable toxicological profile. The compound was subsequently patented by the U.S. Army.

In 1946, the U.S. military immediately began using DEET as a topical insect repellent in places like Vietnam and Southeast Asia.

In 1957, DEET became registered with the EPA as an insect repellent. It soon became widely available to the general public.

DEET insect repellents quickly gained traction as a consumer product. It is believed that the emergence of West Nile Virus resulted in a rapid increase of DEET use. Public fears of other pest-carried diseases have also led to a wider adoption of DEET use, including malaria, dengue fever, yellow fever and Lyme Disease.

In 1998, the EPA estimated that 30% of the United States population use one or more repellents containing DEET a year, and that it was used by approximately 21% of American households. Each year around 200 million people use DEET globally. Over the course of 60 years, billions of people have used DEET to repel insects.

Today, DEET remains one of the most common insect repellents. It can be found in a variety of products, including lotions, sprays, wipes and wrist bands.

Today, DEET remains one of the most common insect repellents. It is seen as the “gold standard” of repellents, even with the discovery of newer compounds such as IR3535 and picaridin. DEET can be found as an active ingredient in a variety of products all over the world in the form of lotions, pump sprays, sunscreens, aerosols, soft wipes and wrist bands.

Efficacy

DEET is effective at deterring a large variety of biting arthropods. Common target pests include fleas, mosquitoes, biting flies and ticks.

DEET is a broad-spectrum repellent. Upon application, it will effectively deter a large variety of biting arthropods. Some of the more common target pests include fleas, chiggers, mosquitoes, biting flies and ticks.

DEET repellents are intended to be applied to skin or clothing. The repellent effect extends out around 1.5 inches from where it is applied.

DEET repellents are intended to be applied topically to skin or clothing.

The repellent effect of DEET only extends out around 1.5 inches out from where it is applied. As a result, it needs to be applied to all areas of exposed skin. Applying DEET to a shirt collar will not protect skin on the neck, nor will application on the nose protect skin on the forehead.

The majority of DEET repellents are labeled for human-use, however a few are registered for veterinary purposes. DEET is sometimes used to prevent bug bites on dogs, cats, horses and other animals.

Concentrations of DEET in insect repellent products can vary greatly, ranging from 4% to 100%. Higher concentrations of DEET have not been seen to provide any more protection than lower concentrations, however, the high concentrations will remain effective for a longer duration.

Generally, low concentrations of DEET remain effective for 3 to 6 hours and high concentrations last for up to 12 hours.

Controlled-release formulations of DEET use an inactive ingredient to bind DEET molecules and release them slowly. This can increase protection time by up to 300%.

DEET’s efficacy and duration can be diminished as a result of washing with water, friction from clothing, sweating, warm temperatures and high winds.

Generally, low concentrations of DEET (20% to 34%) provide three to six hours of protection from mosquitoes. High concentrations of DEET (90% to 100%) offer up to 12 hours of protection. One study showed that a 4.75% DEET preparation lasted for 1.5 hours, 6.65% for 1.9 hours, 20% for 4 hours and 24% for 5 hours. Another study done with mosquitoes showed that a 33% DEET concentration lasts for at least 5 hours without any decrease in efficacy, and a 50% concentration lasts for at least 8 hours without a diminishing effect.

DEET’s cosmetic properties become less desirable as concentrations get higher. Products with 100% DEET can feel oily, sticky and irritating to the skin. In a user acceptability study done in 2001, Australian military members were surveyed on their preference between two repellents, one with 35% DEET and the other with 19.2% picaridin. 94% of the personnel preferred picaridin due to DEET’s discomfort and irritation to skin.

Newer developments have given rise to controlled-release formulations of DEET which extend the repellency duration up to 300%. One such product is 3M ultrathon. These slow-release formulations contain an inactive ingredient which binds the DEET molecules and releases them over 12 hours. As a result, lower concentrations of DEET to be used, leading to reduced odor, greasiness and skin absorption.

DEET’s efficacy and protection time can be diminished as a result of clothing rubbing against treated skin, washing with water, sweating, warm temperatures and high winds. In these circumstances, it is recommended to reapply the insect repellent more often.

The Centers for Disease Control recommends using a 20% to 50% concentration DEET repellent, stating that efficacy plateaus at around 50%.

DEET is believed to be the “gold standard” of insect repellents, providing superior protection from a large variety of flying and crawling nuisance pests.

DEET applied to exposed skin alone provides 99% protection from mosquito bites. Coupled with permethrin on clothing, repellency nears 100%.

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends using a 20% to 50% concentration of DEET, stating that efficacy plateaus at around 50%. Multiple studies corroborate this conclusion. One study on mosquitoes concluded that efficacy peaks at a concentration of 50% DEET. A study on black flies showed that DEET’s efficacy peaked at 25%. Canada’s law further reiterates this, as they have banned all DEET repellents with concentrations over 30%.

DEET is believed to be the “gold standard” of insect repellents. In 1993, Consumer Reports tested a large variety of repellent compounds and found that DEET provided the best results against a broad range of flying and crawling nuisance pests. However, permethrin is superior for deterring ticks.

A military study done in Alaska found that the best protection from insect bites was achieved by combining the use of DEET and permethrin. An extended-release formulation of 35% DEET was applied to exposed skin and permethrin to clothing. Untreated personnel were getting an average of 1188 mosquito bites an hour. When treated with only DEET, they were getting bit four times per an hour (99% repellency). Permethrin alone achieved 93% repellency (78 bites per hour). DEET coupled with permethrin provided 99.9% protection (1 bite per hour).

There have been numerous comparative studies done on the effectiveness of DEET versus other repellent compounds. Results vary by study, but DEET is often found to provide the best results for efficacy and duration. The varying results seem dependent upon species of arthropod, geographic region, and concentrations of the repellent compound used.

One comparative study tested 16 different insect repellents, including DEET, citronella, soybean oil, Avon Skin-So-Soft moisturizer and IR3535. The highest concentration of DEET tested was 23.8% and it was the most effective by a large margin.

In one study, DEET, IR3535 and picaridin were tested against each for repellency to Ochlerotatus taeniorhynchus mosquitoes. The mean percent repellency was 94.8% for DEET, 88.6% for IR3535 and 97.5% for picaridin. Mean protection time was 5.6 hours for DEET, 3 hours for IR3535 and 5.4 hours for picaridin.

Another similar study was done with DEET, IR3535 and picaridin and tested against Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. Picaridin produced the best results, followed by DEET and then IR3535. However, results were mixed for non-target species of mosquitoes encountered during the study.

Mode of Action

The exact repellent mechanism of DEET is still unknown.

The majority of studies show that DEET somehow affects an arthropod’s olfactory (smell) and gustatory (taste) receptors, inhibiting its ability to detect a host.

The exact repellent mechanism of DEET is unknown and remains a topic of on-going research.

Pinpointing the mode of action of insect repellents has proven difficult. This is partially due to the fact that numerous types of substances deter insects. One third of the thousands of compounds tested by the U.S. Bureau of Entomology have shown repellency to some degree. As a result, it is troublesome correlating chemical composition with a repellent effect. It is also unclear whether repellents affect different species of arthropods through the same mechanism of action.

While DEET’s precise mode of action is elusive, the majority of studies demonstrate that the compound somehow affects an arthropod’s olfactory (smell) and gustatory (taste) receptors, making the arthropod unable to detect a host and inhibiting feeding.

Refuted: DEET camouflages the attractants on a host.

Hypothesis: DEET blocks or modifies olfactory receptor neuron responses, inhibiting host detection.

Hypothesis: DEET works as a “confusant”, activating specific ORNs and sending a message to the central nervous system which interferes with other receptors.

Refuted: DEET inhibits an insect’s ability to detect lactic acid in the vapor phase.

Early on, it was known that DEET likely did not camouflage attractants on a host. The repellent mechanism only takes effect in mosquitoes once they get within 4 centimeters of where DEET is applied.

In 1985, it was hypothesized that DEET affects an insect’s olfactory receptors (OR). It was thought that olfactory receptor neuron (ORN) responses could be blocked or modified in the presence of DEET. As a result, mosquitoes would have a difficult time detecting attractants, like lactic acid, on the host.

In 1996, two specific ORNs on the antennae of Aedes mosquitoes were found to be activated by DEET. It was theorized that DEET may work as a “confusant” by sending a message through these neurons to the insect’s central nervous system. This message would interfere with other receptor neurons, hindering their ability to perceive attractants.

In 1999, a study suggested that, by itself, DEET may actually be an attractant and is only a deterrent when applied to a host. It was theorized that DEET becomes active in the gaseous phase, inhibiting an insect’s ability to detect lactic acid on a host. This hypothesis has been laid to rest by another study which proved the effectiveness of DEET in the absence of lactic acid.

Refuted: In the vapor phase, DEET molecules have a fixative, sequestering effect on attractants.

Hypothesis: mosquitoes can directly detect DEET in the vapor phase and then avoid it.

DEET has been shown to affect gustatory receptors and inhibit feeding in insects.

The results of one study in 2008 led researchers to believe that DEET molecules could attach to attractants in the vapor phase, sequestering and neutralizing them. This fixative theory was later refuted by another study.

The same study in 2008 did a sugar-feeding study with mosquitoes. In this feeding assay, both males and females avoided areas where DEET was applied. This gave rise to the theory that mosquitoes directly detect and avoid DEET in the vapor phase with specific odorant receptors.

In 2010, a study showed that DEET suppressed vinegar flies from feeding. It was theorized that DEET activated gustatory receptors in insects, resulting in a feeding deterrent effect. The conclusion was that DEET induces avoidance by affecting both olfactory and gustatory receptors. In 2013, one of the gustatory receptor neurons affected by DEET was identified.

Hypothesis: DEET interferes with warmth and water vapor receptors.

Hypothesis: DEET targets octopaminergic synapses and induces neuroexcitation.

In 2012, four of the stimuli which attract mosquitoes were studied: carbon dioxide, water vapor, warmth and adenosine triphosphate (ATP). It was found that these stimuli induce mosquitoes to seek a blood meal, even in the absence of host odor. When DEET was added to these stimuli, mosquitoes were repelled. Researchers formed a hypothesis that DEET could be interfering with warmth and water vapor receptors.

In 2014, a study done on the neurotoxicity of DEET determined that the compound is likely targeting octopaminergic synapses, inducing neuroexcitation in insects.

Toxicity

DEET

Toxicity Data

| Acute Dermal Exposure | III | I = Highly Toxic | |

| Acute Oral Exposure | III | II = Moderately Toxic | |

| Acute Inhalation Exposure | IV | III = Slightly Toxic | |

| Primary Skin Irritation | IV | IV = Practically Non-Toxic | |

| Primary Eye Irritation | III | EPA Repellent Safety | |

| Dermal Sensitizer | No | CDC Repellent Safety | |

| Carcinogen | No | AAP Repellent Safety | |

| Fish | III | ||

| Aquatic Invertebrates | III | ||

| Birds | III |

The EPA has stated that normal use of DEET does not present a health concern to the general population.

Fears of adverse reactions, to a large extent, are unfounded. With billions of DEET users over 60 years, toxic reactions are remarkably low.

Adults are recommended to use below a 50% concentration of DEET, and children below 30%. Children under two months old should avoid DEET altogether.

DEET has been used by billions of people since its synthesis 60 years ago. In that time, there have been numerous toxicological studies done. These studies have been reviewed by the EPA, resulting in the conclusion that normal use of DEET does not present a health concern to the general public.

There is some controversy regarding the toxicity of DEET, however, to a large extent, these fears are unfounded. With such large numbers of users, over such a long period of time, the occurrence of adverse reactions is remarkably low.

DEET concentrations below 50% rarely have any effect on adults. To minimize the likelihood of adverse reactions, Consumer Reports recommends that adults only use up to 30% DEET in the backyard and up to 50% for camping. The average adult should use no more than two to four tablespoons to cover exposed skin.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends to avoid using DEET on children under two months old. For older children, apply DEET no more than once per day. Parents are recommended to use the lowest DEET concentration they can find, often between 10% to 30%.

DEET’s acute mammalian toxicity is low for all routes of exposure.

DEET has a low human skin absorption rate. Absorbed DEET is rapidly metabolized and then excreted through urination.

DEET’s acute mammalian toxicity is low for all routes of exposure. DEET is categorized as “slightly toxic” for dermal, oral and ocular routes of exposure. It is categorized as “practically non-toxic” upon inhalation.

DEET has a low skin absorption rate and rapidly excretes through urination. In one study, technical grade DEET (100%) was applied to the forearm skin of male volunteers for eight hours. At two hours, the DEET began to absorb. After the eight hour period, DEET’s mean skin absorption rate was at 5.6% (8.4% when combined with ethanol). 12 hours after the application, the majority of the absorbed DEET had been metabolized and excreted. Nearly 100% was excreted within 24 hours. DEET did not accumulate in superficial layers of the skin.

DEET is not a human carcinogen.

DEET shows no signs of any reproductive or development toxicity in humans (mother, fetus or newborn).

The EPA has DEET categorized as a “group D” carcinogen, meaning that it is not classifiable as a human carcinogen.

There are no signs that DEET causes reproductive or developmental toxicity in humans. A study was done where 20% DEET was applied to the arms and legs of women in their 2nd and 3rd trimester of pregnancy. No significant adverse effects were found in the mother or fetus during pregnancy. In addition, there were no adverse effects on survival or development at birth or at the age of one.

The majority of the adverse reactions to DEET are minor and resolve rapidly. Minor reactions include skin and eye irritation.

According to data collected from poison control hotlines, 66% of callers had no adverse reaction to DEET or only experienced minor symptoms that resolved rapidly. A majority of the calls were from inadvertent exposure to eyes, and symptoms included irritation and tearing. 5% of the reports were from dermal exposure, and symptoms included irritation, redness, rashes and swelling. Gastrointestinal problems were reported following accidental ingestion of DEET. These symptoms included oral irritation, nausea and vomiting.

DEET can sometimes cause a tingling and numbness of the lips, mouth and other mucous membranes upon inadvertent exposure. This has recently been attributed to DEET’s mild neurotoxicity, causing a anesthetic-like effect on nerve conduction.

Ingestion of large amount of DEET can cause severe toxic reactions, including coma and death.

Severe toxic reactions can occur upon ingestion of large amounts of DEET. There are five recorded cases of people drinking substantial amounts of DEET. Within an hour of ingestion, the patients experienced seizures, hypotenstion and coma. Two of the patients died and the other three recovered with no long-term damage. A more recent incident occurred when a man consumed 6 ounces of 40% DEET. He died as a result of seizure and cardiac arrest.

There are multiple reports of DEET causing seizures and other nuerotoxic symptoms in young children, however, a clear link to DEET use cannot be determined.

DEET has been reported to be neurologically toxic to a small percentage of young children. Affected children have suffered from seizures, slurred speech, staggering gait, agitation, tremors, convulsions and even death after repeated and extensive coverage of up to 20% DEET to skin. The EPA has reviewed these cases and stated that there is not a clear link to the use of DEET. Regardless, researchers have studied these rare cases but explanations are speculative and unclear. If DEET did cause these reactions, it is estimated that only 1 in 100 million users will experience a seizure.

Severe adverse effects to DEET are rare and causality is speculative. Severe reactions include seizures, tremors, slurred speech, ataxia, encephalopathy, orthostatic hypotension, bradycardia, psychosis, coma and death.

Other rare, yet severe adverse reactions to DEET are ataxia, encephalopathy, orthostatic hypotension, psychosis, bradycardia coma and death. While these reports should be noted, there is not enough reliable data to establish DEET as the cause of the afflictions in many of these cases.

In ecological studies, DEET has been categorized as slightly toxic to freshwater fish, freshwater invertebrates and birds.